Why Redfin, Zillow, and Trulia Haven’t Killed Off Real Estate Brokers

Brad Stone

Other

Redfin founder Eraker was inspired by his own real estate misadventures. Photograph by Robin Stein for Bloomberg Businessweek

Trulia co-founder and CEO Flint intended to work with brokers from the start. Photograph by Mathew Scott for Bloomberg Businessweek

Expedia founder Barton discussed buying Redfin—before launching his own real estate site. Photograph by Michael Todd for Bloomberg Businessweek

Businessweek Redfin CEO Kelman brings fervor of his own. Photograph by Kyle Johnson for Bloomberg

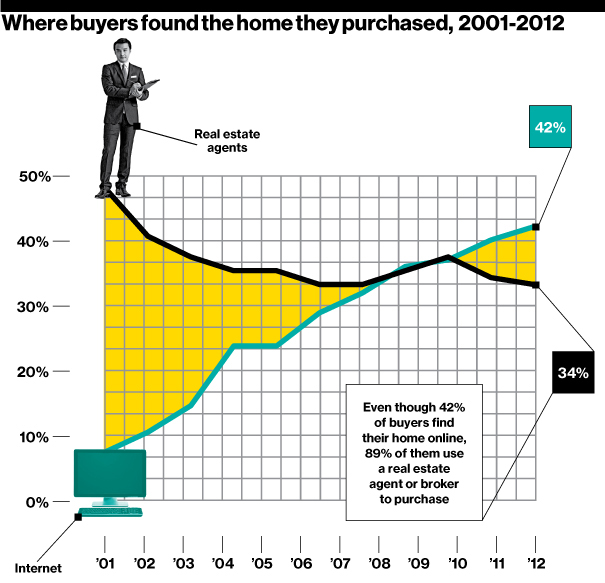

Over the last decade, the Internet has seeped into that bedrock of the U.S. economy: the housing market. A group of growing and mostly profitable websites have sprung up to help guide consumers through what in many cases will be the largest and most nerve-wracking transaction of their lives. Four sites – Redfin and Zillow (Z), based in Seattle, and Trulia (TRLA) and Realtor.com, based in the San Francisco Bay Area – attract 61 million of the 67 million visitors to real estate websites each month in the U.S., according to ComScore (SCOR). They also generate hundreds of millions in revenue and have helped turn buying a house into entertainment a spectator sport that can be enjoyed without darting surreptitiously into random open houses. Ninety percent of consumers now start their real estate journeys on the Web, according to the National Association of Realtors.

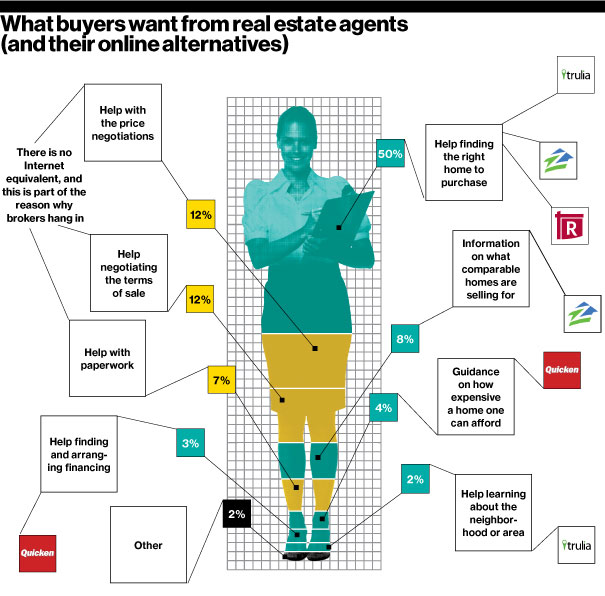

It all looks at first glance like the same kind of electronic marketplace that has eliminated travel agents, decimated classified ads, depressed stock brokers, and taken the swagger out of car dealers, but it hasn’t dented the fortunes of real estate brokers. A majority of buyers and sellers still wind up working with traditional brokers, one on each side of the deal.

Not only have brokers resisted the attack by the Internet’s real estate sites but their fees remain stable. Real Trends, a research firm, reports the average commission paid to the buying and selling brokers was 5.4 percent of the price of a home in 2011, up from 5 percent in 2008. (The seller’s agent collects the commission from the seller and then splits it evenly with the buyer’s agent.) That’s considerably higher than the median rate in markets abroad, where there may only be one agent involved in the transaction, such as the U.K. (a 1 percent to 2 percent fee), Germany (3 percent to 6 percent), Israel (4 percent), and the Netherlands (1.5 percent to 2 percent), according to a 2007 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. “Ten years ago almost no one started their home search online. And yet none of that value has come back to the consumer,” says Glenn Kelman, Redfin’s chief executive officer.

Redfin has been trying to change the equation since its founding nearly 10 years ago, and its story partly explains how one species of middleman has hung on with such tenacity. Unlike other real estate websites, Redfin employs its own agents who trudge through open houses, pound for-sale signs into lawns, and work directly with buyers and sellers. Departing from the model of traditional brokerages, however, Redfin pays its agents with an annual salary, rather than commissions, and ties bonuses to customer reviews of their performance.

It can save customers a lot of money, but Redfin, which had more than $50 million in revenue last year, has grown more slowly than competitors such as Zillow and Trulia, which display listings and other information and then pass customers off to traditional real estate agents, who finish the deal. Redfin represents less than 3 percent of buyers and sellers in Seattle, its hometown, and has a negligible market share in the 20 other major metropolitan areas where it operates. It is also not yet profitable, partly because of the cost of hiring brokers and setting up offices when it enters new markets.

Economists have long been perplexed by the resilience of the real estate agent. Theory suggests that the relationship between agent and buyer or seller is far from optimal, and that conflict is often borne out in practice. At the root of the difficulty is what economists call the Principal-Agent Problem, which describes the diverging, often conflicting, interests of the principal (the customer) and the agent representing him or her. (Since agents bear much of the costs of selling a house, in the time they spend hosting open houses and touring with clients and the money they spend advertising property, they’re rewarded for pressuring clients into selling quickly and accepting suboptimal offers, or, in the case of a buyer’s agent, for allowing the client to pay too much.) In 2008, Stanford University economics professors B. Douglas Bernheim and Jonathan Meer published the results of their study of nearly 30 years of house and condo sales on the university campus. They found that an owner’s use of a broker to sell their property reduced the eventual selling price by 5.9 percent to 7.7 percent, compared with homes sold by the owner directly.

Yet only 9 percent of homes were sold directly by owners in 2012, down from 13 percent in 2008, according to the National Association of Realtors. As one might expect, members of the housing industry argue that people simply value the expertise and service that agents can provide and are nervous about venturing out on their own or trusting an online discounter for the most complicated transaction of their lives. “We will never be a point-and-click industry,” says Phil Faranda, who runs J. Philip Real Estate, a 14-agent brokerage in Westchester County, N.Y. “You will always need a trusted adviser to ensure that you get the best terms possible. The stakes are so high. If you want to do a do-it-yourself project, build a hovercraft.”

Sellers come back despite the expense, too. In 2008, Steven Levitt and Chad Syverson, economists at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business, published two papers on the topic of real estate commissions, seeking to address the question of why discount brokers and for-sale-by-owner transactions have failed to steal sales from real estate agents. They found that there’s a subtle collusion in real estate that separates it from industries like stock trading and air travel. Two agents, not one, are required to sell a house – one representing the buyer, the other the seller. “Needing two agents to cooperate in a transaction allows a full-service agent to punish discount agents,” Syverson says. “It also allows full-service agents to punish other full-service agents who cooperate with discount agents.” As a result, an agent can steer clients away from for-sale-by-owner properties or from homes represented by discount brokers.

David Eraker, Redfin’s founder, was trying to buy a condominium when he became frustrated by the inability to research the location of properties online, and by the irrationality of broker commissions that remain fixed regardless of fluctuations in the housing supply or the level of competition among agents. Eraker, who dropped out of the University of Washington’s medical school for a career in software design, thought he could topple the traditional brokerage model. “We had a lot of religion around the fact that consumers were not being well served by existing business models,” he says.

In 2002, working from Eraker’s apartment in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, Eraker and his partner, Michael Dougherty, an electrical engineer with a degree from Yale, struck upon the idea of displaying homes for sale on an online map. This was before the introduction of Google Maps (GOOG) or Microsoft’s (MSFT) Bing Maps, and the early Redfin engineers spent much of their time licensing mapping data and figuring out how to allow users to zoom down from aerial views into specific neighborhoods to see the homes for sale, without requiring the entire Web page to reload in a browser. Redfin also decided to start hiring its own real estate agents to help its customers close transactions.

The site, which went live in 2004 with an interactive map and for-sale listings in the Seattle area, attracted attention and cultivated local users but struggled to raise venture funding. “A lot of venture capitalists were going off to ask real estate agents if they thought what we were doing was a good idea, which is not necessarily the right question to be asking,” Eraker says. Meanwhile, employees were not getting paid and the company was running up credit-card debt.

Eraker’s next-door neighbor during the summer of 2004 was Sami Inkinen, a Finnish Stanford MBA student completing a two-month internship at Microsoft. During backyard barbecues and over several lunches at a nearby Thai restaurant, Eraker says he confided in Inkinen and showed him the Redfin website and business plan. Inkinen then returned to the Bay Area to finish his degree at Stanford—and with a classmate co-founded Trulia in the Stanford University library.

At the time he was talking to Inkinen, Eraker was contacted by Rich Barton, the founder of Expedia (EXPE), which had played a lead role in vaporizing travel agents. Barton and his partners were contemplating their next startup and, like everyone else in Seattle, had seen the Redfin prototype. Barton met Eraker and Dougherty at his offices near Union Station in downtown Seattle, invited them to lunch, and even discussed purchasing the startup. Barton instead created his own site, Zillow, at the end of 2004. In his first round of funding from two Silicon Valley venture capital firms, Barton raised $32 million. “My personal belief is that both Zillow and Trulia got their ideas for map search from us,” says Eraker. He also recognizes that while both companies may have been inspired by Redfin, they opted for very different and, in retrospect, more accessible business models.

Inkinen says he and Trulia’s co-founder and CEO, Pete Flint, never considered circumventing brokers. Their original idea was to scour the listings on brokers’ own real estate sites, just as Google crawls the Web, and organize all that data on a single customer-friendly site. It was essentially an advertising site for agencies, and consequently, many brokers now voluntarily send them their listings. “You don’t finish your doctor’s appointment or surgery online, just like you don’t complete legal documents for an IPO online,” Inkinen says. “I never saw buying a home becoming a transaction like buying a book on Amazon (AMZN).” He also says he and Flint were already thinking about starting a business in real estate when he spoke to Eraker and describes those conversations as “entrepreneur talking to entrepreneur. He was battling all the usual things, trying to start something and figure out a business model.”

For his part, Zillow founder Barton says he and his partners were also planning a Web business in real estate when they heard of Redfin and met with Eraker. “It had been 10 years since the Internet took off, and we couldn’t believe how the industry hadn’t changed much,” Barton says. At first the early Zillow employees contemplated holding online auctions for homes as a way to disrupt the housing market before deciding that was impractical. “It was obvious to us, regardless of how relatively frustrated consumers were with the whole process, how important the agent relationship was to customers. No robots were going to eliminate the agent,” Barton says.

Over the next few years, Eraker would watch with dismay as both Zillow and Trulia raised tens of millions in venture capital at higher valuations – mainly because both companies were building purely digital businesses and leaving the hand-holding, and the big fees, to the brokers. Zillow and Trulia, in effect, decided to enable the traditional way of doing business in real estate rather than fight it.

Redfin, meanwhile, struggled. In early 2005, with the company accumulating debt and employees going unpaid, Redfin finally attracted interest from a San Francisco-based venture capital firm, but as it got close to concluding a deal, Eraker and his colleagues weren’t getting along. Alarmed, the VC firm pulled out at the last minute. After 18 months of unpaid work, the company was back to square one. Most of the engineers left the firm, and Dougherty, Redfin’s co-founder, defected to Zillow. Humbled, Eraker had to move the company out of its shared office space and back to his Capitol Hill apartment. “We had been in the desert starving, and here comes $2.5 million—and then the next day, poof, it was gone,” says Eraker. “I screwed up a lot of stuff. It was rock bottom.”

Eventually, Madrona Venture Group, a Seattle venture capital firm, resuscitated the company in the fall of 2005 with a $750,000 investment and recruited Kelman. Soon after, Kelman became CEO and Eraker left the company to travel and decompress after four intense years. Redfin would face considerable challenges getting other venture capitalists to invest, particularly in the shadow of Zillow and Trulia’s breakaway growth. But in Kelman, Redfin had found someone with just as much fervor for changing the way homes are bought and sold.

When Kelman replaced Eraker at Redfin, the company thought it had a way to solve the Principal-Agent Problem, lower commissions, and diminish the significance of the agent in the home-buying process. During its first few years as a venture-backed company, it asked customers to conduct most of their transactions online and employed agents only to review final deals. It even charged customers $250 every time they wanted to get up from the computer and actually tour a house.

The payoff for buyers and sellers was in radically lower fees. Instead of collecting the 3 percent commission from the seller, Redfin charged sellers a flat $3,000 fee, paid at closing, for listing and marketing a home. When Redfin represented the buyer, the company, in the role of agent, would receive the standard 3 percent commission on the purchase price from the seller but then refund about two-thirds of that to the buyer, or about $6,000 for a $300,000 house.

It was disruptive, and Kelman relished the chaos. “Real estate, by far, is the most screwed up industry in America,” he told CBS News’s 60 Minutes in 2007. “We feel like things that Amazon or EBay (EBAY) or Yahoo! (YHOO) have done in other industries, we can do for the real estate industry.” Kelman now regards that statement as an error. “The biggest mistake I made in starting out at Redfin was bringing some Silicon Valley swagger into a traditional industry,” he says. “It was unnecessarily provocative.”

Redfin encountered all the forms of industry bias predicted by the Stanford economists. It got angry phone calls and e-mails, and agents steered customers away from its properties. In 2007, Washington’s Northwest Multiple Listing Service determined that one of Redfin’s blogs, which offered frank reviews of properties written by staff journalists, violated its policies against critiquing customer listings. It fined the company $50,000 and threatened to pull its MLS access. Redfin had to shut down the blog. Now it allows only licensed agents to post reviews of properties, and it gives its clients the ability to veto or delay such posts, which seems to have appeased the brokers.

The company also discovered that its customers really did want more hand-holding. As it struggled to make its model work, Redfin had to hire more agents to assist customers in every stage of the buying and selling process. It scrapped the idea of charging for home tours—customers hated that—and because of the increases in service, it overhauled its fee structure. For sellers, the flat fee is gone; they’re now charged 1.5 percent of the sale price of their home. As before, the seller, even if he is using Redfin, must pay the buyer’s broker the usual 3 percent. Buyers are still treated to a refund upon Redfin’s collection of the buyer-side broker commission, though Redfin has gradually lowered that amount as it has added services. “The problem with our original model was that people couldn’t get into houses, they wanted advice. At some point we realized that we had to become a service company,” says Kelman. “We thought we could make the business more virtual than it was.”

Redfin still does a lot of things differently. Apart from the unusual way it pays its agents, it offers a virtual “deal room” that helps customers navigate the maze of complex paperwork and, unlike Zillow and Trulia, draws its listings directly from the MLS. This, Redfin says, allows it to display 20 percent more agent-listed properties than non-broker websites.

In February the company hired agents and began showing listings in five new markets, including Houston, Raleigh-Durham, and New York City’s Bronx borough (it already operates in Queens, as well as Nassau, Suffolk, and Westchester counties). It also says it plans to double its roster of agents this year to meet rising demand. Kelman says a Redfin IPO is unlikely this year though possible in 2014.

So far, Redfin hasn’t convinced many people that brokers, or their 6 percent take on most deals, are in any real danger. Last October, at a Seattle technology conference, an audience member asked Spencer Rascoff, Zillow’s CEO, if sales commissions were ever going to decline. “There are other startups that are trying to break down those agent commissions, and I think most of them will fail,” he said. Rascoff said later in an interview that “consumers don’t really care about commissions. They say they care, and they talk a big game in the off-season. But when push comes to shove and it comes time to sell their home, the transaction is so infrequent and so highly emotional and expensive – and consumers are so prone to error – that they turn to a professional.”

Economists, like the University of Chicago’s Syverson, watch and wait for a real change in the market. “The Chicagoan in me says there is so much money on the table that someone will figure it out eventually,” he says. “But I will admit, I’ve been impressed with the resilience of the old model.”

©2013 Bloomberg L.P.